Chief reporter ELLEN GRINDLEY reviews a new book detailing how former slave owners settled in Devon

FORMER slave owners moved to Devon from across the country and empire to retire in coastal resorts, a new book shows.

Men and women who had enslaved men, women and children in the West Indies made their home, or second or third home, in the county after emancipation in 1834. Some came for short periods after slavery was outlawed and others lived here for decades.

They largely overlooked inland market towns and favoured Sidmouth, Budleigh Salterton, Exmouth, Dawlish, Teignmouth, Torquay, Ilfracombe and Lynton.

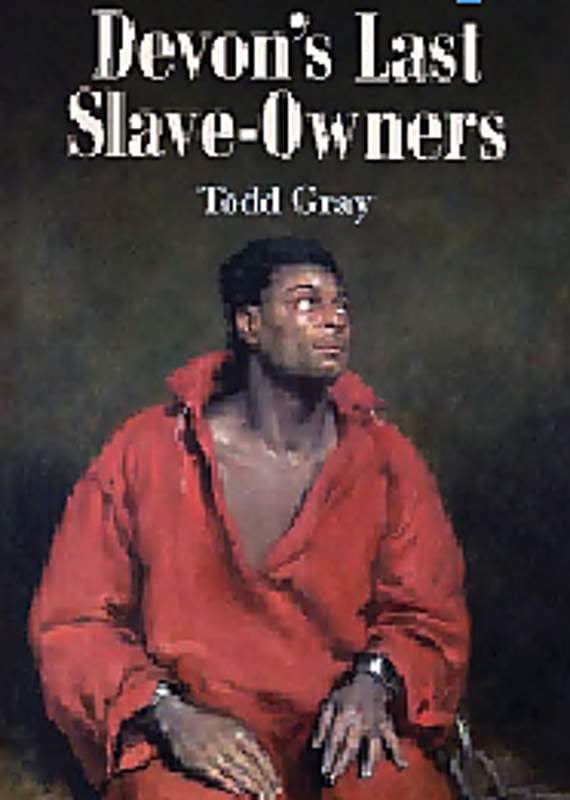

A new book, Devon’s Last Slave-Owners, by Dr Todd Gray, focuses on Devonians who owned enslaved people across the empire at the time of emancipation.

It is the UK’s first county study of slave-ownership.

It establishes that on August 1 1834, when the Slavery Abolition Act took effect, there were 34 slaveholders resident in Devon.

On that day an estimated 34,407 men and women in the UK and the empire were compensated by the government for the loss of their enslaved people. No compensation was given to the men, women and children who had been enslaved.

The Devon slave-owners owned 4,957 people, 0.8 per cent of all 636,358 men, women and children who were freed from their enslavement.

These Devonians were granted £138,000 (or roughly £9,000,00 in today’s money) in compensation.

Around half of this compensation was given to three men who had moved to Devon: Thomas Teschemaker received £15,668 3s, Henry Porter had £35,960 14s 8d and his brother Thomas had £19,295 8s.

James Hackett, of Newton Abbot, spent his working life from the 1820s through to the 1850s as a local official in Demerara.

In 1871 his widow referred to him as having been in the Colonial Civil Service.

The Irishman had died two years earlier in Newton Abbot and was noted then as being formerly of Demerara and Boulogne-sur-Mer. Hackett appears to have moved to Devon shortly before his death.

His widow lived at Courtenay Terrace in Newton Abbot and their son remained in the town through his adult life.

Hackett received compensation of £2,247 15s 11d (£152,403.48) for 42 individuals. In 1832 he had registered 57 enslaved people on the Onderneeming estate in Demerara.

Edward Butler Taylor, of Teignmouth, an attorney, was in his native Barbados in 1836 when he had his award of £1,079 14s 5d (£73,206.48) for 43 enslaved people on Arthur Seat Estate.

In 1817 his eight household slaves were Isaac (black, 42, born in Africa), Simon (black, 22, Barbadian), Diana (black, 28, a Creole from Grenada), Adel (black, 28, a Creole from Martinique), Juliet (black, five months old, a Creole from Martinique), Fanny (Coloured, 42, Barbadian), Kitty Ann (Coloured, 7, Barbadian) and Charlotte (Coloured, 4, Barbadian).

Twelve years later, in 1829, he owned 39 human beings.

Taylor relocated to Bristol in the late 1830s before settling down at West Teignmouth. By 1851 he was at Tuckers Garden with his married daughter and two servants.

Taylor died two years later in Teignmouth and was buried in Bristol.

In the generation that followed emancipation some 50 additional former-slave holders moved to Devon, many of them retired to newly fashionable coastal resorts for the rest of their lives.

Some rented holiday accommodation from a few months to several years.

Others had second homes in the county and it was at this time that the era of second-home owning in Devon began in earnest.

The research also shows that these former slaveholders were part of the influx of well-heeled people who were largely born outside Devon that populated the county’s new seaside resorts.

Among the 34 owners were Devonians such as Elizabeth D’Urban of Topsham whose father and father-in-law were leading officials in the West Indies.

She inherited a forced-labour estate in Grenada and received the equivalent of £204,327.98 in compensation for the loss of her enslaved people.

A small number came to Plymouth through their existing naval connections and a handful resided in Exeter which then had a reputation as being an inexpensive city in which to retire.

A small number were mixed-race descendants of West Indian slave-owners and they lived in Dawlish, Great Torrington and Plymouth. Some slaveholders brought enslaved people with them to Devon where they were then free. Most appear to have stayed in Devon but one man returned to Jamaica after his dismay at experiencing a winter in the county.

The book shows some slave-owners led opulent lifestyles such as the Porter family, who lived at Winslade House in Clyst St Mary.

Thomas Daniel, known as the `King of Bristol’, owned a third home in Stoodleigh and was among the most prosperous men to be compensated: he had £68,512 8s 7d (£4,645,231.76).

Dr Gray, honorary research fellow at the University of Exeter, said: ‘Many of Devon’s slaveholders were resident in the county for short periods. Their life stories show they were born across the globe, and came from a variety of social backgrounds.

‘Some families who had owned slaves had existing connections to Devon but others came to this part of Britain because of the warmer climate or most likely chose Devon because money went further than it did in more developed parts of the country.

‘Many led truly peripatetic lives and only a handful remained rooted to one place.

‘They were not just well travelled but lived in a number of counties if not countries. Some former slave owners stayed in Devon for less than a year, others for several decades.

`I have dedicated my working life to the study of Devon and am attempting to introduce some basic historical facts.

‘I hope this will replace any assumptions that have been made.

‘We now have a baseline in understanding who was then involved in slavery. The figure may not be as high as leading industrialised parts of England but it reflects Devon.

‘It has taken me 37 years to read the 500 books necessary to understand this subject along with reading thousands of newspaper pages and more than 100,000 documents.’

Most former slave-owning families led quiet and anonymous lives but a few rose to considerable local prominence.

A few individuals, such as Lord Rolle and William Templer Pole, were from their births leading figures in Devon.

Some served as High Sherifs, town mayors or on the committees of local charities.

Dr Gray has not found evidence that the county’s ‘great families’ then owned slaves, with the exception of the Rolles, the Poles of Shute and the Carys of Follaton.

On emancipation Devon’s largest landowner, Lord Rolle, received £4,333 6s 9d, the equivalent of £293,805.92 today.

It appears that his family lost money rather than gained through slavery and he attempted for many years to free the enslaved.

Eventually nearly 400 Bahamians were freed early and unusually Rolle gave them his land where their descendants remain on the land. Many then took the surname Rolle whereas in Devon the family line died out.

Devon’s Last Slave-Owners; Plantations, Compensation and the Enslaved, 1834 is published by The Mint Press and is available through any book-seller or direct from Stevenbooks.

-played-a-pivotal-role-in-the-pi.png?width=209&height=140&crop=209:145,smart&quality=75)

Comments

This article has no comments yet. Be the first to leave a comment.